The Lone Woman

Juana Maria

of San Nicolas Island

"The song that I will sing is an old song, so old that none know who made it. It has been handed down through generations and was taught to me when I was young. It is now my own song. It belongs to me." --Geronimo

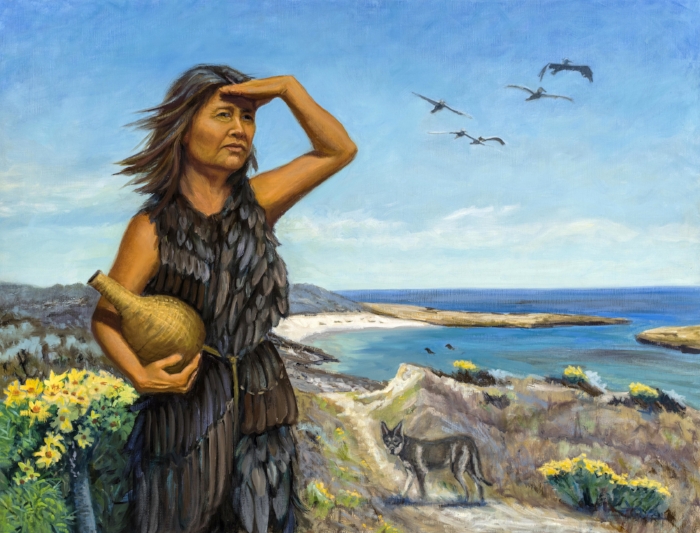

The Lone Woman 26x34 Oil By Holli Harmon See the painting at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History

Imagine growing up on remote San Nicolas Island during the nineteenth century. Children there, like everywhere, learned songs and stories about the world around them. On the island, these stories were likely about their ancestors or about the animals of their island and ocean world. The children were familiar with ocean tides and seasonal variations, and with the night sky. They knew the best places to collect kelp and sea lettuce, mussels and abalones. They knew how to fish. Perhaps a few of them even had dog companions.

On the clearest days, one can catch a glimpse of the mainland—60 miles from San Nicolas. The Nicoleños had trade relationships and social interactions with other islanders, including those from Santa Catalina. Other visitors to the island during the 1800s included American, Russian and Native Alaskan fur traders and hunters who captured sea otters for their pelts.

San Nicolas Island is where Juana Maria was born and lived for most of her life. Several historic events had a profound impact on her life. In 1814, perhaps close to the time that she was born, a group of Kodiak hunters came to the island and fought with the island men, killing most of them. Juana Maria must have grown up in a community that remembered this catastrophic incident and grieved for their loved ones. In the 1830s, she became pregnant and gave birth to a son. Soon after, in 1835, the small remaining community, just eighteen people, was brought back to the mainland as directed by the Mission fathers. As the story goes, Juana Maria stayed behind when she realized that her son was not on the ship. She later recounted that the child did not survive. And so, that is how she came to live on the island alone. For the next eighteen years, she would continue to make her subsistence-based living on her island home without contact from the outside world

On the mainland, these years were a time of great change. The Mission era saw the drastic decline of the Indian population, in part due to disease. After the Mexican War of Independence in 1822, Spanish rule ended and California became a Mexican territory. With Mexican land grants, cattle ranching became a way of life for many families. The Mexican American War of 1846-1848 ended with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The California Gold Rush began in 1848, and California achieved statehood in 1850. The City of Santa Barbara was founded the same year, with some 2,000 residents.

In 1853, Captain George Nidever, sailed to the island at the request of the Mission to find her. According to Nidever’s accounts, he and his small crew encountered Juana Maria and also spent several days there hunting otters. They found her to be in good spirits, living with her dog companions.

When Nidever brought her to Santa Barbara, few of the local Chumash may have been familiar with her language.The Nicoleños who had left the island eighteen years earlier were taken to San Pedro and they dispersed in the Los Angeles area. They may not have known of her rescue from the island. Today, researchers believe that her language was related to language groups found to the south. Genetic evidence suggests there was intermarriage between groups of the northern and southern Channel Islands as well as the mainland.

In Santa Barbara, Juana Maria lived with Nidever, his wife, Sinforosa and their children. Juana Maria was baptized and received the name that we know her by today; her Indian name is unknown. By all accounts, she happily welcomed her transition to life in Santa Barbara. She shared her songs and had many visitors, including the mission padres, who always found her to be in good humor. However, after only a few weeks of living on the mainland, she became ill and passed away. She is buried in the mission cemetery.

Her life story is unique and remarkable; she survived on her island alone for nearly two decades. As one of the last surviving Indians of San Nicolas, she is also symbolic of the decimation of a culture.

Researchers today continue to learn more about nineteenth century life on San Nicolas Island through archaeological evidence and the detective work of searching through historical records. Recent excavations by archaeologists on San Nicolas Island have revealed the large cave shelter where Juana Maria most likely lived. Two redwood boxes were also discovered that may have belonged to her and contained items such as abalone pendants, knives and fishing implements, and small stone carvings of animal figures.

"I am an old woman now...and our Indian ways are almost gone. Sometimes I find it hard to believe that I ever lived them."--Waheenee, Hidatsa

To learn more about San Nicolas Island and Juana Maria there are several resources: The National Park Service Blue Dolphin site includes links to information about the Scott O'Dell book, Island of the Blue Dolphin, as well as information on recent research. Absalom Stuart’s 1880 article, A Femal Crusoe, recounts conversations with George Nidever. Research on what happened to the Indians who left San Nicolas Island in 1835 is available in a paper by Morris, Johnson, Schwartz, Vellanoweth, Farris and Schwebel: The Nicoleños in Los Angeles: Documenting the Fate of the Lone Woman's Community.

See the painting at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History

Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History

Chumash Indian Hall Open everyday 10-5pm.

The Portrait Painting Process

Holli became increasingly intrigued with the story of the Lone Woman after conversations with archaeologist Steve Schwartz. Schwartz discovered the large cave shelter where it is thought that Juana Maria lived. In creating her painting of Juana Maria, Holli began by drafting a series of sketches based on first hand descriptions of the Lone Woman. She also conferred with anthropology and historian colleagues who discussed different characteristics including facial structure and variation in facial characteristics. The depiction of Juana Maria’s clothing is based on descriptions by Nidever of the feather cloak that she was wearing at the time of his visit to the island.

By Katherine Bradford

Sojourner Kincaid Rolle

“The word is powerful. It can evoke emotion, it can tell about a rock, or a tree. It can be used to instigate anger, to quell anger, to lament love, to give love; it touches you in the heart. Whether spoken or written it conveys how you feel. You may not even be the poet but [it resonates] with what you bring to it, your experience.” --Sojourner Kincaid Rolle, Poet Laureate, Playwright, Environmental Educator and Peace Activist

Sojourner Kincaid Rolle, oil on canvas, 26x34" by Holli Harmon

Poet Laureate

Sojourner reflects on Percy Shelley’s famous quote, “Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” She says, “The implication is that we’re speaking truth. What we observe—we try to get to the essence of it.” From a young age, she has continually reflected on the impact that poetry can offer.

Sojourner’s poetry stems from her remarkable experiences. Much of her work clearly is rooted in our region and its beauty, however her life’s journey has also given her a unique perspective as a social activist.

Her love of the natural world is heard in a multitude of poems she has written over the decades, and she takes pride in her role as a poet of place and as an environmental educator. This passion has been recognized by her community where she has served as a Poet Laureate of Santa Barbara, as well as a Poet-in-Residence at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History.

She has also received many accolades including being named a Local Hero by the Santa Barbara Independent; Outstanding Woman of Santa Barbara County by the Santa Barbara County Commission for Women; American Riviera Woman Entrepreneur of the Year; and a Commendation for Community Service by the Santa Barbara County Board of Supervisors.

“I truly appreciate being the Poet Laureate of Santa Barbara. I’ve been overwhelmed by the response of the community. This is a community that loves poetry.”

Santa Barbara

“When I first came to Santa Barbara I loved going to the Bird Refuge, East Beach and Ledbetter. I love the natural environment here, up and down the coast. Every place I’ve lived in California has felt like home.”

Nearly four decades ago, Sojourner and her beau, Rod Rolle, made a road trip from their home in North Carolina to California. Their initial destination—an aunt’s home in Lompoc. Sojourner was headed to law school at Berkeley, and Rod—after two years had passed—to the Brooks Institute of Photography in Santa Barbara. Three years after graduating from law school, Sojourner joined Rod in Santa Barbara. Celebrating 30 years of marriage, they are among Santa Barbara’s most prominent creative couples. “We each are able to pursue our own lives as artists and, we also have dinner together [almost’ every night].”

In Santa Barbara, Sojourner discovered a close-knit community of poets and participated in variety of poetry activities. During those early years, she helped to organize festivals and regular readings featuring poetry andbegan teaching poetry workshops in the schools. “I became more of a poet than I’d ever been before. I decided that I wanted my life to be about the arts” and she served for ten years on the Santa Barbara County Arts Commission.” On her path to becoming Poet Laureate, she has taught poetry to generations of young people, published critically received articles and commentaries on subjects ranging from the environment and civil rights to love and time. She has seen her work performed on the theatrical stage.

She served as producer and host for the public access television show “Outrageous Women,” beginning in 1989 and continuing for 7-8 years, interviewing fascinating guests from diverse backgrounds. It was about this time that, at the invitation of the such entities as the Independent, Arts & Letters, and The Lobero Theater , she began conducting interviews with notable artists who came to town. These have included such luminaries as James Baldwin, Maya Angelou, Odetta and Hugh Masekela….

Sojourner has continually served as a community activist—a peace activist. Her renowned contributions to civic poetry are a vital part of her work, however she is also engaged in mediation, and she has made critical contributions in her work as a civil rights activist—our interview takes place on the day after she has participated in the Women’s March in Los Angeles. Millions of women participated in cities all over the world. “It was one of the most glorious days—you knew you were sharing in a historic moment.” Her life-long activism has been inspired by her family and community.

“We hold in common a dream of harmony. What binds our hearts is our hope for peace and our vision of a shared humanity.” –SKR in The Task of Our Time.

Early Life and Work

Sojourner was born in Marion, North Carolina, and, from age five, lived with her grandmother who was active in their church and in the community. With a deepened appreciation of African-American history, she added “Sojourner’ (after suffragist and abolitionist Sojourner Truth)) to her name at age 30. The influence of her family, especially her grandmother’s influence as an community leader continues in her life today. “I attended a segregated school in North Carolina during the fifties. My early memory is of not starting first grade on time because my grandmother and others were boycotting the school until the school board fired the principal. For the most part, my family protected me from face–to-face encounters with racism. Nevertheless, it was unavoidable. I've written about some of these encounters in my story subtitled, ‘Growing Up Colored in the Segregated South.’”

Her experience with poetry began at a young age. “At one assembly, like a talent show, my grandmother urged me to recitea poem I knew by heart.. .I was five years old. At my church, as well, I would regularly hear and recite a poem to the congregation. Most of the Black schools taught Speech and were famous for oratory competitions. In eighth grade, she participated in her first oratory competition at a regional Sunday School convention. “I recited from memory, ‘On Democracy’ by Arnold J. Toynbee. I didn’t win but I did give my speech!”

It was also in eighth grade that she had the lead in the class play.

Sojourner carries her southern culture with her. It is a way of viewing the world. “When I meet other southerners we have many common references, including references from the bible and folklore.”

Her growing up years included time with her mother in New York as well as time with her father abroad. I grew up in a military family. From first to eighth grade I lived with my grandmother in Marion. In ninth and tenth grade , I lived with my aunt’s family in Fort Bragg and I went to E.E. Smith High School . Then I moved with my dad and his new family to Germany where I graduated from Munich American High School.

“Living overseas, we read magazines like Ebony and Jet to try and keep up with what was happening ‘‘back in the world’,’ as we called the states. It was in a photo on the cover of Jet that I recognized a guy from E.E. Smith sitting-in at the Woolworth’s\lunch counter in Greensboro. I thought, ‘ that’s what I’d be doing if I were home.’ I wanted to be a part of the movement against segregation and discrimination. My grandmother had set that example for me.”

Now iconic photos and film footage depict the sit-ins of African American students who protested ‘Whites only’ policies by sitting at Woolworth stores’ lunch counters. The first sit-in took place in Greensboro, attracting a storm of national media attention, and was replicated by students and others throughout the south, resulting in the store changing its policies, as well as many other institutions. The impact of the Greensboro sit-ins contributed to the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Other historic events made an impression on Sojourner as a young woman, such as the murder of Emmett Till, the 1963 March on Washington , and the bombing of the the Birmingham Baptist Church, to name a few. “I was also influenced by Charlayne Hunter-Gault—hers is a famous civil rights struggle. She integrated the School of Journalism at the University of Georgia as one of the first two black students to attend.” Decades later, Sojourner interviewed the Pulitzer-prize winning journalist on her local public access show, "Outrageous Women”.

“To me, I didn’t see much future in the south in our little town (now our town has grown.) I embrace it. I was on the train to New York on my 18th birthday. A few months later, I got a job at the New York Public Library, where I worked with many college students. They encouraged me to continue my education.”

In the late 1960s she moved to D.C. and worked for as a receptionistat a radio station. She was working there when Martin Luther King was killed. That experience became a subject for one of her plays. That experience also led her to volunteer for the Poor People's Campaign. Moving back to Brooklyn, she later worked for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference as a staff member. “From that time on, I feel that I was on the path for the lifelong struggle for civil rights. My grandmother had set that example for me.” She continues today as a board member of the local Martin Luther King Jr. Committee.

After 30 years in the military, Sojourner’s father retired to start a business in their hometown. She moved to North Carolina to help him and to eventually attend UNC Charlotte. She had become involved in the children’s rights movement and majored in criminal justice with an emphasis on juvenile delinquency. Her intention was to attend law school and wasaccepted at UC Berkeley.

“In law school, I was disappointed with the world of legal practice, and even asked for a leave of absence to consider my future. My Dean told me, “you need to decide whether you want to be a crusader or a lawyer.” She eventually chose poetry and peacemaking. Subsequently, Sojourner worked for 20 years with City At Peace, a theatre group that specialized in the arts and conflict resolution.

“A friend invited me to read a poem for her college graduation.” This resurrected her lifelong journey into poetry and marked her emergence into public expression. “Now I call myself a public poet.”

Song of Place

A part of Sojourner’s living legacy during the past two decades is her gift to young poets through the Song of Place Poetry Project. Her work has included teaching poetry in the schools and she has inspired a multitude of young poets to share their worlds. She invites poets of all ages to write about their surroundings and has emphasized that. She considers herself a poet of place. “Place is the backdrop for every poem or story and informs both the exposition and the narrative.”

To experience Sojourner’s wit and wisdom, catch her at a poetry reading, check-out her Facebook page and find her on the world wide web, or go to the library or bookstore and immerse yourself in her songs of place found in her celebrated books. You may be inspired to write a poem yourself!

--Katherine Bradford

Where the Hum Begins

I am in a place

where water rolls across the stones

rippling in ranges

too high for human tones to mimic

It is a place

where mountains loom over land

so low it is almost level with the sea

In the distance

I can hear water falling fast

from a high plateau

brushing the slope of the solid earth

at sharp angles, diving

into the flow

where it falls, a continuous splash issues

It is at this place I dwell

between calm and tumoil,

between yang and yin

between memory and amnesia

between today and tomorrow

between sate and want

In the magic hour

when the tide changes

In the right moment

where each second becomes the next

in the pull of the moon

while the water ebbs and flows

In this place, I stand

on land rocky like a river

land where boulders abide

deep within the soil

It is a place of peace

even as on the billowing sea

--Sojourner Kincaid Rolle

Erik and Hans Gregersen

““I feel people will adapt to the changes taking place. Hirschman’s principle of the ‘Hiding Hand’ applies here: We tend to underestimate the emerging issues, but we also underestimate our ability to resolve the issues. ””

Erik and Hans Gregersen, Mixed Media Triptych, 24x42

Originally from Denmark, Jens Gregersen was one of Solvang’s founders. As a pastor, he helped to establish the town’s first Lutheran Church. Little did he know that his American grandsons would return to Denmark as children, travel the globe for work, and finally settle on the family ranch in the Santa Ynez Valley.

Brothers Erik and Hans Gregersen always knew that they would someday return to the valley. Having worked around the world, Hans reflects, “The Santa Ynez Valley is the best place to live; the people here are wonderful and the scenery is gorgeous.”

EARLY LIFE AND CAREERS

Their father was a petroleum geologist who was involved in the discovery of the Cuyama oil fields. Their mother was one of the first women to obtain a Ph.D. at Yale, and later worked as a librarian at the Huntington Library. Immediately after World War II ended, Gulf Oil was looking for a U.S. trained geologist to manage its oil and gas exploration program in Scandinavia. Their father was picked to do this job and they moved to Denmark in August, 1945. As schoolchildren in Denmark, Erik and Hans became fluent in Danish and enjoyed Danish holiday traditions, food and music. This was the beginning of their global perspective. Living in a country recovering from the ravages of WWII gave them a unique experience, not only to appreciate their American heritage but to continue to grow as universal citizens. After returning to the U.S. for high school and college, they each embarked on careers that took them abroad again.

Erik studied engineering and business, earning an MBA from Harvard. He spent 15 years in various management assignments with FMC Corporation, which specialized in commercial machinery related to the food and agricultural industries. He worked in the U.S., England, and South Africa. With this background, he and a friend from England started a produce labeling business after acquiring manufacturing and marketing rights to the patented labeling system that was invented in Ventura. “We had 85% of the market worldwide.” After a 30 year career in the food and agricultural machinery industry, he chose to return to the family ranch in 1997.

Younger brother, Hans, studied forestry, social sciences, and economics, earning a Ph.D. in Economics of Natural Resources at the University of Michigan. While still in graduate school, he began working with the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization in Rome. As a professor at the University of Minnesota, he developed a program in international natural resources policy and continued lifelong work with the UN, the World Bank, the InterAmerican Development Bank, and many other international groups. After early retirement from the Universityin 2000, he served on the Science Council and headed the impact assessment Unit of the World Bank-chaired Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). “The CGIAR is a major entity that does agricultural and natural resources research to benefit the less developed countries and the poor around the world. It has centers all over the world. I visited and worked with all of them, including centers in Nigeria, Cote d’Ivoire, Kenya, Syria, Sri Lanka, India, Malaysia, Philippines, Indonesia, Colombia, Peru, Mexico and other countries. The centers have made and continue to make major contributions to global agriculture, food security and natural resources management and conservation.” Erik and Hans exemplify what it means to be global citizens. “You learn how to deal with different kinds of people, with different languages, cultures and customs,” observes Hans.

Reflections on the Santa Ynez Valley

Changes in recent decades include growth of the wine industry and commercial development by the Chumash tribe. Hans reflects, “There were no vineyards in the early days; cattle ranches are less common now and the cost of land is high. Normal young people can’t afford to purchase land here anymore.”

The Gregersen brothers retired from their highly successful careers and moved with their wives to Solvang where they enjoy their families and grandchildren who live both locally and farther afield. It is interesting to note that both of these men made their careers in agriculture and land management. These are the same motivators that brought a large group of immigrants from Denmark to the U.S. and eventually Solvang. Although their career paths deal with agriculture and land management at the international level, land is still a resource that plays a significant role in their lives today. Their respective industries (agriculture and land management) have new millennial challenges. The cost of land and availability of water threaten agriculture as development outpaces the economic return from growing food and availability of water.

Erik and Hans have a “world” of experience between them and continue to use their knowledge both in service of their immediate community and the global community. They are heavily involved with improving the quality of life locally and globally. Today, Erik runs the ranch and is involved with non-profits, including the Elverhoj Museum, “I’m passionate about preserving the history of the Danish community.” He is also active with The Land Trust for Santa Barbara County and the California Rangeland Trust. “Our grandparents had 2200 acres, cattle and also beans and barely. When they passed, there were too many heirs and taxes soour parents’ generation was forced to sell. If we had the ability [at that time] to put a conservation easement on it we could have kept it together. That’s what The Land Trust allows.”

Hans continues to work with various groups on deforestation and global forest policies, and is currently working on global forestry contributions to the new UN 2030 Agenda on Sustainable Development. When asked about the challenges facing the Santa Ynez Valley, Hans reflects, “I feel people will adapt to the changes taking place. Hirschman’s principle of the ‘Hiding Hand’ applies here: We tend to underestimate the emerging issues, but we also underestimate our ability to resolve the issues. ”

By Katherine Bradford

Richard and Thekla Sanford

Sometimes, you need a "do over". Richard and Thekla were so early in the project that we did not have a professional videographer. So we came back and got to meet with Richard and Thekla Sanford, and their daughter Blakeney in their new Alma Rosa Tasting Room and on the old Rancho Jabili.-

See below for the new video.

History of Wine

Wine has an ancient history, with a long cast of characters including the Roman God Bacchus, best known for his Bacchanalia festival. In our own California history, Father Junipero Serra planted our first sustained vineyard at Mission San Juan Capistrano two hundred years ago. One hundred years after that, Jean-Louis Vines was the largest wine producer in Los Angeles and his peer, Agoston Haraszthy, a Hungarian soldier, promoted vine planting over much of Northern California, including Sonoma Valley. All of these men were immigrant adventurers, each fulfilling their own quest.

I think there is something in our genetic code or our own Manifest Destiny that has brought all of us here to the Central Coast. Either, within ourselves, or in the temperament of our fore fathers, we are adventurers, free thinkers and/or entrepreneurs. These are all common traits you find in gold miners, immigrants and hippies, all of which have made up our collective California culture.

Let me focus on a very specific time in our state’s history. In 1965 Berkley was the home to Flower Power, people wore Birkenstocks and marched for civil rights. Meanwhile our nation was in the midst of the Vietnam war which left our country questioning the establishment and authority. These two countercultures converged to shape the next century. Imagine graduating as a Geography student at UC Berkeley in 1965 and then suddenly be drafted into the Vietnam War for the next 3 years. This was Richard Sanford ‘s reality. After his service as a naval officer, Richard wanted to work with the land and felt agriculture would help him reconnect with his former life. He had been introduced to a Burgundy wine during his time with the military and thought, “Out of all different agricultural products, why not grapes?” Combining his knowledge of geography, he began to study our climate records for the last 100 years and compare them to the Burgundy region of France. It was here he discovered our transverse mountain range created the perfect environment for the Pinot Noir grape.

This history only underscores Richard Sanford’s adventurous and entrepreneurial spirit. With incredible insight, the birth of our central coast wine country was established in 1970 when he planted the first Pinot Noir vines in what is now the Santa Rita Hills. California is now the 4th largest wine producer in the world and garners a $61.5 BILLION impact in our state economy.

Meanwhile, the other half of this story, was moving west. Thekla Brumder, a nice girl from Wisconsin, had spent her childhood outdoors, in tune with nature and investigating the wonders of her grandparents’ dairy farm. As a young adult, she stopped off at the University of Arizona to pick up a BA in Art History and a few minors in Spanish and Italian. She then spent her 20‘s in the Colorado Rockies before moving to Santa Barbara.

Fast forward to 1976. This is when Richard and Thekla, meet on a sailing adventure in Santa Barbara. In the same year, there is a blind wine tasting in Paris with a panel made up exclusively of French wine experts. Six out of the 9 judges ranked California wines as the best in the world. Two years later, Thekla and Richard marry in 1978 and start Sanford Winery by 1981. Together, they have produced award-winning wines for over 30 years. Their latest venture is

Alma Rosa Winery and Vineyards

Using their life’s experience, they have created a business that produces high quality wines. It also is the benchmark for organic, sustainable farming and is environmentally responsible to the land, it’s employees and customers.

And it is here ,on their home ranch, Rancho El Jabali, that the Sanfords were sharing their mutual life story in a lovely room designed by Richard and built sustainably from bales of hay and stucco. Thekla humorously recollects about how Richard stuck a thermometer out of the window while driving his car through the Santa Ynez Valley in order to measure the temperature on this hillside or on top of that range. This was to find the perfect location for the first vineyard. Likewise, Richard gives Thekla all the credit for starting their organic farming practices, an offshoot of their family vegetable garden. The El Jabali Vineyard was the first OCOF (California Certified Organic Farmers) certified vineyard in Santa Barbara County.

While the fire crackles in the fireplace and radiates its warmth throughout the room, I observe a couple who have shared a common goal throughout a life that has been filled with hard work, successes and challenges. They have a thoughtfulness about their legacy and future. Their efforts and business enterprise reflect what is important to them and what they stand for.

Remember at the beginning of this story, I talked about the spirits of adventure, free thinking and entrepreneurship. These common attributes are what make this couple so dynamic and forerunners in both winemaking and conservation. They both share a love of the land and this has been the foundation in their success as vintners and conservationists. While Richard brought his understanding of the land and agriculture to winemaking, Thekla brought her love of nature and community. The arc of their commitment starts with organic farming and sustainable agriculture and includes ecological packaging, green building, wildlife protection and culminates in the slow food movement, which addresses the quality of the food we eat, where it comes from and how this affects the world. They were even honored by the Environmental Defense Center as Environmental Heroes. Most recently, they recieved the inaugural Sanford Award for Sustainable Stewardship from the Edible Communities. All the while, they make award winning wine! And Richard Sanford was just added to the Vintners Hall of Fame at The Culinary Institute of America.

Their incredible commitment to our environment while operating an enlightened enterprise is just the beginning of their contribution. I always find their support and sponsorship at so many of our non profit events. They have consistently made one good decision after another to operate with integrity, be good stewards of the land, and serve humanity. Cheers!

By Holli Harmon

ElseMarie Lund Petersen

“I didn’t have to change when I came here. I think California allows you to be who you are.”

ElseMarie Lund Petersen, oil on canvas 18x24 by Holli Harmon

ElseMarie Petersen

ElseMarie came to Solvang as a tourist from Denmark in 1987. On that trip she met Aaron Petersen, who she married one year later. Aaron’s family has deep roots in the Santa Ynez Valley. Together they have raised four children there and have built several successful businesses, including Chomp and the Greenhouse Cafe. "We like to eat dinner together as a family but sometimes it's hard when you run two restaurants."

When their children were young, ElseMarie and Aaron made time for extended travel in Europe. They spent two months each in Denmark, France and Italy, and the children gained an appreciation for their own family history as well as for other cultures. They learned new languages and skills that have been useful in their lives and professions.

Growing up in Denmark, ElseMarie heard many stories about Solvang from her father who participated in a farm exchange program; he worked for two years on an Alamo Pintado property in the 1950s. They discovered her mother had relatives in Solvang when her family first visited Solvang together when she was a teenager.

Reflecting on the differences in life between Denmark and Solvang, she observes, “Denmark is a little more traditional. You always wish you could slow things down here. We had dinners that lasted until 1 or 2 a.m. Here, people leave at 9:30 or 10:30.” ElseMarie remembers long dinners and chatting with friends in the kitchen; after the dishes were done, conversations would continue over dessert long into the night.

In addition to working with her family's business, ElseMarie has recently become the manager of Copenhagen House. She is passionate about Danish design. "Danish architecture and designs are used all over the world." The Lego Group, Arne Jacobsen's Egg Chairs, and Louis Poulsen lighting designs are all examples of a Danish aesthetic that focuses on functional design and clean lines. This aesthetic was influenced by the Bauhaus school and extended to building design as well as furniture. Famous examples of Danish design in modern architecture are the Copenhagen Opera House and Sydney Opera House.

ElseMarie notes, "In Danish houses, the walls are often white; maybe this is because it is often dark or rainy outside. Danes have a fondness for hyggeligt; the translation to English is like coziness indoors." This is sometimes described as a feeling of conviviality, such as that found in fireside chats or over a shared meal. She observes that here in Solvang her family likes to spend time outdoors too. She is also a road cyclist and observes, "The Santa Ynez Valley is the most beautiful place," a sentiment echoed by all of our Portrait subjects that call the SYV home.

Thinking back to her first memories of Solvang in the seventies, she remembers, "There wasn't as much tourism.” Although most visitors come from southern California, Solvang is known around the world, and has over a million visitors each year. Many of the towns of the central coast depend on tourism as an industry. “Even though there's more traffic now we embrace tourism but we still have a small town feel. We have a lot of families here; people are involved in their children's lives. There is a nice sense of community.”

She shares pride in her adopted hometown of Solvang and the organizations that work to promote Danish culture in our region, such as the Danish Sisterhood. "I didn't have to change when I came here. I think California allows you to be who you are."

To experience Danish culture close to home, from learning about pioneers in the valley to sampling delectable baked goods, fine beers and savory meals to demonstrations of artisanal crafts, music and dance, visit Solvang during Danish Days, or anytime!

By Katherine Bradford

Luis Ramirez

-“A very small amount of people feed the world.”

Luis Ramirez

A Farmer and so much more

Luis Ramirez, oil on canvas By Holli Harmon

The fertile Santa Maria River Valley yields some of the most important crops in the state—lettuces, broccoli, strawberries, grapes. These vital crops are harvested by migrant workers who are proud of their work and in their ability to provide for their families. State and federal policies are in place to guard the safety of these workers and the food they handle. On the fields are hands-on agricultural managers like Luis Ramirez. “Our food safety program ensures that produce is harvested and shipped in a hygienic and safe manner.”

Luis works for Rancho Harvest, a company that is contracted by farmers to provide labor and hauling to processors or directly to stores. “Training crews is a big piece of it. I go to the crews and do visual inspections. I have an enormous amount of respect for the workers. I’ve tried harvesting lettuce, broccoli, berries—it’s humbling.”

Before being hired as a manager, Luis attended Cal State Long Beach, where he earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree. “Doing a drive along the fields with my friends from Cal State Long Beach is eye-opening. The general public doesn’t know what people should know; a very small amount of people feed the world.”

Luis was born in Guadalajara, Mexico. “My earliest memory is of crossing the river on my father’s shoulders, but most of my memories start here.” His parents were hired to work on a Santa Ynez Valley ranch and he grew up with his brother attending the local schools including Santa Ynez Union High School. “The school was about 40% Hispanic and 60% Anglo. I grew up poor but I had a unique experience, growing up on a ranch, riding horses. When you’re a kid, you just want to fit in.” Luis shares that he felt like he was raised in two cultures; the culture of his parent’s Mexico and the SYV ranch culture. “You’re culturally rich that way.”

His major influences were his strict parents who instilled values of respect and hard work. “Respect is built into our language. Me dio la oportunidad, y abrió muchas puertas saber que comunicarme con la gente.”

He had an early passion for art. “My dad was not excited about me changing my major to art but my parents were always supportive.” Luis transferred to CSULB from Alan Hancock College. While at CSULB, he attended a summer program in Italy and then had a year of education abroad at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts in China.

“I’ve always been able to learn things. I branched out to wine [working at Bridlewood Estate Winery and Fiddlehead Cellars], and eventually agriculture. It was tough to get hired [with an art degree]. Even stronger than a degree is your ability to talk to people and get things done.”

In his early 30s, Luis is a master painter. “I paint my experiences--family, the ranch, field agricultural operations. I’ve been painting the same thing since I can remember; the agricultural community in California and a bit of the immigrant experience.”

“I paint the field workers in sunlight; they are squinting. I use a Spanish palette.” Using just four colors to mix his paints, Luis captures a range of light that retains the rich colors of the area. “I have no political agenda. I just paint field workers.”

Luis has worked for Rancho Harvest for two years. “It gives me a level of security.” In a typical day he visits several crews in the Santa Maria area, but his territory also includes Salinas, Bakersfield, Oxnard and Coachella. “Broccoli, cauliflower, strawberries, wine grapes. This is our food supply. I don’t know what else is more important. I’m just a food guy. What a cheap labor force we are. We keep food on the table and at a reasonable price.”

“H-2A [seasonal agricultural worker visa program], I think is the future of agriculture. The program allows us to recruit in Mexico and then [workers] return after the season is over. There’s a labor crunch. There is not enough labor in the Santa Maria Valley. Working in the fields is an act of necessity. If you have few options for work it’s a default; there are monetary benefits for working here.”

“There is a necessity to provide for your family. I don’t think the workers say, I’m here to provide food for the world. They say, I’m here to provide for my family. It’s a point of pride.”

As alluded to in Holli’s portrait, Luis is part of fabric and heart of the Santa Maria Valley. His experiences bridge the cultures of the valley. Moreover, in his role as an agricultural manager, his work to ensure safe food affects all of us who live in the central coast region and beyond.

When asked what he would like the public to know, he reflects, “be connected to the food supply. Understand that months of preparation go into it. Remember the people that work it.”

By Katherine Bradford

Erik and Hans Gregersen

Solvang's Founding Family

“The Santa Ynez Valley is the best place to live; the people here are wonderful and the scenery is gorgeous.” Hans Gregersen

Erik and Hans Gregersen, Mixed Media Triptych, 24x42

Originally from Denmark, Jens Gregersen was one of Solvang’s founders. As a pastor, he helped to establish the town’s first Lutheran Church. Little did he know that his American grandsons would return to Denmark as children, travel the globe for work, and finally settle on the family ranch in the Santa Ynez Valley.

Brothers Erik and Hans Gregersen always knew that they would someday return to the valley. Having worked around the world, Hans reflects, “The Santa Ynez Valley is the best place to live; the people here are wonderful and the scenery is gorgeous.”

Early life and careers

Their father was a petroleum geologist who was involved in the discovery of the Cuyama oil fields. Their mother was one of the first women to obtain a Ph.D. at Yale, and later worked as a librarian at the Huntington Library. Immediately after World War II ended, Gulf Oil was looking for a U.S. trained geologist to manage its oil and gas exploration program in Scandinavia. Their father was picked to do this job and they moved to Denmark in August, 1945. As schoolchildren in Denmark, Erik and Hans became fluent in Danish and enjoyed Danish holiday traditions, food and music. This was the beginning of their global perspective. Living in a country recovering from the ravages of WWII gave them a unique experience, not only to appreciate their American heritage but to continue to grow as universal citizens. After returning to the U.S. for high school and college, they each embarked on careers that took them abroad again.

Erik studied engineering and business, earning an MBA from Harvard. He spent 15 years in various management assignments with FMC Corporation, which specialized in commercial machinery related to the food and agricultural industries. He worked in the U.S., England, and South Africa. With this background, he and a friend from England started a produce labeling business after acquiring manufacturing and marketing rights to the patented labeling system that was invented in Ventura. “We had 85% of the market worldwide.” After a 30 year career in the food and agricultural machinery industry, he chose to return to the family ranch in 1997.

Younger brother, Hans, studied forestry, social sciences, and economics, earning a Ph.D. in Economics of Natural Resources at the University of Michigan. While still in graduate school, he began working with the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization in Rome. As a professor at the University of Minnesota, he developed a program in international natural resources policy and continued lifelong work with the UN, the World Bank, the InterAmerican Development Bank, and many other international groups. After early retirement from the Universityin 2000, he served on the Science Council and headed the impact assessment Unit of the World Bank-chaired Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). “The CGIAR is a major entity that does agricultural and natural resources research to benefit the less developed countries and the poor around the world. It has centers all over the world. I visited and worked with all of them, including centers in Nigeria, Cote d’Ivoire, Kenya, Syria, Sri Lanka, India, Malaysia, Philippines, Indonesia, Colombia, Peru, Mexico and other countries. The centers have made and continue to make major contributions to global agriculture, food security and natural resources management and conservation.” Erik and Hans exemplify what it means to be global citizens. “You learn how to deal with different kinds of people, with different languages, cultures and customs,” observes Hans.

Reflections on the Santa Ynez Valley

Changes in recent decades include growth of the wine industry and commercial development by the Chumash tribe. Hans reflects, “There were no vineyards in the early days; cattle ranches are less common now and the cost of land is high. Normal young people can’t afford to purchase land here anymore.”

The Gregersen brothers retired from their highly successful careers and moved with their wives to Solvang where they enjoy their families and grandchildren who live both locally and farther afield. It is interesting to note that both of these men made their careers in agriculture and land management. These are the same motivators that brought a large group of immigrants from Denmark to the U.S. and eventually Solvang. Although their career paths deal with agriculture and land management at the international level, land is still a resource that plays a significant role in their lives today. Their respective industries (agriculture and land management) have new millennial challenges. The cost of land and availability of water threaten agriculture as development outpaces the economic return from growing food and availability of water.

Erik and Hans have a “world” of experience between them and continue to use their knowledge both in service of their immediate community and the global community. They are heavily involved with improving the quality of life locally and globally. Today, Erik runs the ranch and is involved with non-profits, including the Elverhoj Museum, “I’m passionate about preserving the history of the Danish community.” He is also active with The Land Trust for Santa Barbara County and the California Rangeland Trust. “Our grandparents had 2200 acres, cattle and also beans and barely. When they passed, there were too many heirs and taxes soour parents’ generation was forced to sell. If we had the ability [at that time] to put a conservation easement on it we could have kept it together. That’s what The Land Trust allows.”

Hans continues to work with various groups on deforestation and global forest policies, and is currently working on global forestry contributionsto the new UN 2030 Agenda on Sustainable Development. When asked about the challenges facing the Santa Ynez Valley, Hans reflects, “I feel people will adapt to the changes taking place. Hirschman’s principle of the ‘Hiding Hand’ applies here: We tend to underestimate the emerging issues, but we also underestimate our ability to resolve the issues. ”

By Katherine Bradford

Mike Lopez & Kathleen Marshall

Samala Chumash Siblings, Santa Ynez Valley

"Now we can give back."

Portrait of Mike Lopez, oil on canvas, 36x36

Portrait of Kathleen Marshall, oil on canvas, 36x36

“In our native language, we are called Samala.” The Santa Ynez Valley is home to the Samala people, historically known as the Ineseño Chumash. Siblings Kathleen Marshall and Mike Lopez are leaders in the Samala community. In their personal stories, we can glimpse the development of the modern Samala in terms of economic prosperity and cultural renewal. Kathleen is a gaming commissioner and a credentialed teacher of the Samala language -- she carries the stories and traditions that are central to Samala history and identity. Her brother Mike serves as a business committee member.

Their family has always been part of the Santa Ynez Valley. Their ancestral villages include Kalawshaq, which was located near the current reservation, and Soxtonokmu, on Figueroa Mountain. Their great-great-great-great grandmother was Maria Solares, who worked with anthropologist J.P. Harrington to record the Samala language, including many stories and the names of village sites.

The stories many of us tell may be meaningful to our friends, and perhaps to our children. It is inspiring to think that the stories and language of Maria Solares, recorded so long ago, continue to resonate in the community of her descendents.

Kathleen and Mike have warm memories of visiting their grandfather's house on the Santa Ynez Chumash reservation. "We were here all the time; we'd play in the riverbed and eat meals together." They participated in many cultural events at the old tribal hall and made frequent field trips to Zaca Lake, a place that is central to many Chumash stories.

"Our house was built next to my grandfather's house." Kathleen and Mike were raised on the reservation during the 1970s. Their memories include challenges as well. Like other families on the reservation, they experienced poverty and racial discrimination.

During the course of the 19th and 20th centuries, the Samala language was nearly lost. Natives were told to assimilate, to fit in, not only by outsiders but often by their own family members. Many natives were sent to boarding schools where they were forbidden speak their own languages. With cultural renewal movements in the 1960s to regain tribal rights, many Indian communities made inroads into improving conditions for their communities. In today’s generation, appreciation of cultural diversity continues to increase, but there is still a lot of education that needs to take place.

For the Samala people, economic conditions improved with the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988, which recognized tribal sovereignty and allowed gaming on federally recognized reservations. The Chumash Casino was established in 1994, and expanded into a new facility with an entertainment complex in 2003. Resort operations also include the Hotel Corque and several restaurants. Revenue generated from the casino and related enterprises has helped the Samala people grow their business interests, and in turn they are also able to give back to the community.

“We’re an economic leader; we give to places that helped us, now we help them,” Mike observes. The tribe supports dozens of causes in the community including Cottage Hospital and the Unity Shoppe. Gaming revenue also helps to support education efforts, including Kathleen’s work to sustain traditional culture.

Kathleen has studied the Samala language and is now credentialed to teach the language. “A group of us began working with linguist Dr. Richard Applegate several years ago. He helped us to learn our language.” In turn, Kathleen is bringing the language and traditions to a new generation, and uses Samala with her own children at meals.

“We also have Camp Kalawshaq which is held every summer for tribal children. The tribe holds language and culture classes for their youth twice a week.” Kathleen enjoys teaching non-native kids too, “Some of them think we live in teepees.” She also serves on the museum advisory committee. The tribe is in the process of designing a museum to share their culture.

Cultural pride extends to community events and ceremonies. The tribe sponsors an inter-tribal pow-wow each year, which is attended by Indians and others from all over the country, and Chumash Culture Days, which provides an opportunity for Santa Barbara area neighbors to become more familiar with the Chumash and other California natives. Among the highlights of the year are preparations for the tomol crossing; the rowing of a traditional plank canoe to Santa Cruz Island.

“We’re a big family; some people are involved in education, business, investments…,” shares Mike. There is also an environmental and sustainability council. When asked what is unique about their community, Kathleen and Mike both mention the land. Zanja de Cota Creek runs through the middle of the reservation and is a constant reminder of their connection to the land. At the head of the creek is a spring near which the old village was located; it is called Kasaqunpeq’en (where it stops).

Chumash heritage today includes the legacies that people like Kathleen and Mike are building, from the classroom to the boardroom. Kathleen and Mike are representative of the modern Samala. They are each working hard to ensure the economic vitality of their community and the continuity of Samala traditions.

Stephanie Mutz

“A great day of fishing is flat water, warm sun, and lots of seafood.”

Stephanie Mutz, Sea Urchin and Whelk Diver

President of Commercial Fishermen of Santa Barbara

Stephanie Mutz, oil on linen, 24x36

Stephanie Mutz appears to be a quintessential California girl. Raised in the surfing culture of Newport Beach, her dad was a key influence in her love of the ocean. “I grew up surfing, waterskiing on the ocean, and free-diving for dinner. We’d catch lobster, crab, and scallops. We just took what we needed – I still practice that.”

Stephanie is a businesswoman and commercial fisherman; as a woman she is an anomaly among her “salty dog” colleagues. “As a fisherman I’m very lucky – I’ve gotten the opportunity to learn from a lot of fishermen in the community. I think a lot of people appreciate my political efforts. I’m grateful for being part of this community.” Stephanie has earned respect through her advocacy for commercial fisherman and for their sustainability efforts.

“Fishermen want certain regulations – the seafood in our own backyard is the most responsibly caught in the world. I give a lot of accolades to the fishermen in our community.”

Stephanie first came to Santa Barbara twenty years ago to study marine biology at UCSB. “I was given good opportunities.” As part of her studies she lived in Tahiti for a couple of years, “I got paid to count fish – damsel fish, different species. After I came back to Santa Barbara I got a good job counting fish and invertebrates from Oregon to Mexico, mostly on the Channel Islands.” She was involved in collecting data for long-term ecological surveys. “When you start knowing why things happen, what they’re called, it’s more interesting. I’m still learning.”

After completing her undergraduate degree she went to Australia to work with tropical ecologist Howard Choat at James Cook University. Her research subject was the Acanthurids, which include the tropical surgeonfish. She studied otoliths (fish earbones) to look at age-size frequencies. “The otolith has rings that you can count, like tree-rings.”

“I went to grad school so that I could teach at a college.” Her return to California coincided with the recession, a time when college classes were being cut. “I got a job as a deck-hand and got into the politics of fishing. My interest was in fisheries. I went to a lot of meetings – one day in fins and the next in heels. Fishing, meetings, education, outreach – I saw a future in fishing. I focused on developing a business.”

“Fishermen are an important part of our community because we provide a healthy protein source. Done properly, it’s extremely sustainable. We can only take enough for the species to reproduce – we’re learning the thresholds to limit our take. That can be difficult if the price isn’t adjusted as well. I need to take into account how much it costs to go fishing and set aside [funds] for boat repairs and bad weather.”

As president of Commercial Fishermen of Santa Barbara, she is a respected advocate for her community and for sustainable practices. She also remains actively involved in education and outreach, and teaches part-time in the Ventura Community Colleges.

When asked what she’d like to see in the future of fishing, Stephanie has some clear ideas. “I’d like to see a fishing heritage – a local wild source, an industry that fishes responsibly. I’d like to see consumers educated about where their seafood comes from. Seafood is confusing – it could be less confusing if it passes through fewer hands. For the next generation of fishermen, I hope for plenty of seafood. With good management there’s a future in this business.”

“I fish up north to Point Conception, to Santa Cruz Island and Santa Rosa. It’s a dangerous job. If you lose a colleague – that’s the worst. You can have broken boats, bad weather. [You can] get skunked – the fish aren’t there. It’s not a certainty. My life is the same as fishermen a hundred years ago. I appreciate the freedom, I’m the boss. Every day is different.” Stephanie fishes alone in the Santa Barbara Channel, from her 20 foot panga. She collects each whelk individually, sometimes diving 40 feet.

“I go to my secret spot, I have a bag, a rake, and a measuring gauge. I open a few [urchins] to see if the quality is good – I fill the bag. I sell to restaurants, sometimes to a processor.” To savor the best uni, it must be absolutely fresh. “Alum is used as a preservative for uni – it changes the taste.” Urchin fresh from the sea is a salty and sweet delicacy.

“We have a Community Supported Fishery, which I co-founded. Our customers sign-up for 12- weeks of fresh local seafood. They know where it was caught and who caught it. Along with the catch we include management policy information and recipes.”

Another local resource is the Saturday fish market at the Santa Barbara harbor. Stephanie suggests, “Talk to your local fishermen, find out where your seafood comes from.” You may even meet Stephanie there.

For more about Stephanie and Community Supported Fishery (CSF) sustainable seafood, see these websites: www.seastephaniefish.com and www.communityseafood.com.

By Katherine Bradford

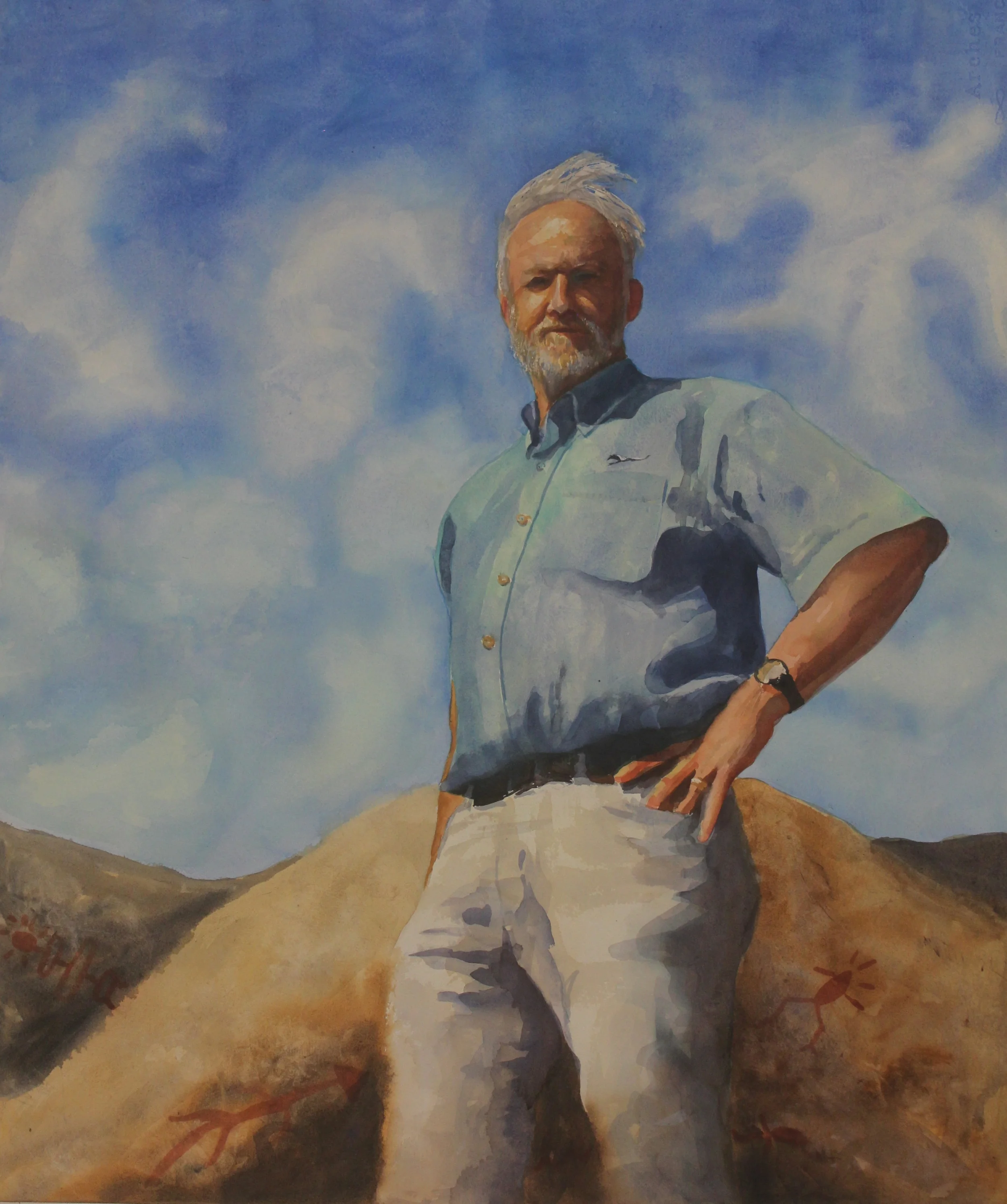

Dr. John Johnson

“I was curious.”

Dr. John Johnson began his career as an archaeologist working for the U.S. Forest Service, doing surveys in the hills and canyons of the Santa Barbara backcountry. It was while doing this work that he came across ancient sites—ceremonial areas, rock art sites, and abandoned villages. “I wondered, who lived here?” This question has been the key to unlocking many of the doors that have been opened by this anthropologist over four decades.

Professor Shuji Nakamura

Shuji Nakamura, Inventor

Where is the best place to live? That is the question renowned inventor Shuji Nakamura asked his colleagues when he decided to emigrate. Where you live determines who your children will grow up with, and what you have nearby access to in terms of culture, education, recreation, health care, and work. For Shuji, the draw to Santa Barbara included its world-class university and technological hub.

Genoveva Gonzalez

“I remember the taste of sweet watermelons. My father was a farmer, he grew corn, watermelon, pumpkins, squash. I remember following the plow--planting seeds.” Genoveva was born in Xilitla Guerrero, a little town that was off the grid when she was growing up. There were no cars. “We went to the next town to buy things we need.”

David Dewey

Ernestine De Soto

Anapamu, Malibu, Sisquoc, Sespe, Point Mugu -- these Chumash names are familiar to many of us on the Central Coast—we are not only surrounded by Chumash history here but we also have many neighbors who share Chumash heritage. Archaeological and genetic evidence suggests that Chumash ancestors were among the earliest peoples in the New World, settling on the Central Coast and Channel Islands as early as 13,000 years ago.

Mike and Mimi deGruy

The Golden Ratio

The tides are in our veins. –Robinson Jeffers

“Do what you love and you will become good at it,” Mike was known to say.

His passion for the ocean took him from the Gulf Shores of his childhood home to ultimately explore the world's oceans and record what he saw on film. With a career as a marine biologist and curator of invertebrates already established, Mike went on to become an acclaimed documentary filmmaker.

Elizabeth Poett

One of the iconic images of central California is rolling golden hills dotted with oak trees and cattle. We are home to cowboys and cattle ranches. And this is where Elizabeth Poett’s story begins. Elizabeth is the great-great-great-great-granddaughter of Jose de la Guerra. You may recognize this name if you live in Santa Barbara.

Richard and Thekla Sanford

Richard and Thekla Sanford, oil 30x36

History of Wine

Wine has an ancient history, with a long cast of characters including the Roman God Bacchus, best known for his Bacchanalia festival. In our own California history, Father Junipero Serra planted our first sustained vineyard at Mission San Juan Capistrano two hundred years ago. One hundred years after that, Jean-Louis Vines was the largest wine producer in Los Angeles and his peer, Agoston Haraszthy, a Hungarian soldier, promoted vine planting over much of Northern California, including Sonoma Valley. All of these men were immigrant adventurers, each fulfilling their own quest.

I think there is something in our genetic code or our own Manifest Destiny that has brought all of us here to the Central Coast. Either, within ourselves, or in the temperament of our fore fathers, we are adventurers, free thinkers and/or entrepreneurs. These are all common traits you find in gold miners, immigrants and hippies, all of which have made up our collective California culture.

Let me focus on a very specific time in our state’s history. In 1965 Berkley was the home to Flower Power, people wore Birkenstocks and marched for civil rights. Meanwhile our nation was in the midst of the Vietnam war which left our country questioning the establishment and authority. These two countercultures converged to shape the next century. Imagine graduating as a Geography student at UC Berkeley in 1965 and then suddenly be drafted into the Vietnam War for the next 3 years. This was Richard Sanford ‘s reality. After his service as a naval officer, Richard wanted to work with the land and felt agriculture would help him reconnect with his former life. He had been introduced to a Burgundy wine during his time with the military and thought, “Out of all different agricultural products, why not grapes?” Combining his knowledge of geography, he began to study our climate records for the last 100 years and compare them to the Burgundy region of France. It was here he discovered our transverse mountain range created the perfect environment for the Pinot Noir grape.

This history only underscores Richard Sanford’s adventurous and entrepreneurial spirit. With incredible insight, the birth of our central coast wine country was established in 1970 when he planted the first Pinot Noir vines in what is now the Santa Rita Hills. California is now the 4th largest wine producer in the world and garners a $61.5 BILLION impact in our state economy.

Meanwhile, the other half of this story, was moving west. Thekla Brumder, a nice girl from Wisconsin, had spent her childhood outdoors, in tune with nature and investigating the wonders of her grandparents’ dairy farm. As a young adult, she stopped off at the University of Arizona to pick up a BA in Art History and a few minors in Spanish and Italian. She then spent her 20‘s in the Colorado Rockies before moving to Santa Barbara.

Fast forward to 1976. This is when Richard and Thekla, meet on a sailing adventure in Santa Barbara. In the same year, there is a blind wine tasting in Paris with a panel made up exclusively of French wine experts. Six out of the 9 judges ranked California wines as the best in the world. Two years later, Thekla and Richard marry in 1978 and start Sanford Winery by 1981. Together, they have produced award-winning wines for over 30 years. Their latest venture is

Alma Rosa Winery and Vineyards

Using their life’s experience, they have created a business that produces high quality wines. It also is the benchmark for organic, sustainable farming and is environmentally responsible to the land, it’s employees and customers.

And it is here ,on their home ranch, Rancho El Jabali, that the Sanfords were sharing their mutual life story in a lovely room designed by Richard and built sustainably from bales of hay and stucco. Thekla humorously recollects about how Richard stuck a thermometer out of the window while driving his car through the Santa Ynez Valley in order to measure the temperature on this hillside or on top of that range. This was to find the perfect location for the first vineyard. Likewise, Richard gives Thekla all the credit for starting their organic farming practices, an offshoot of their family vegetable garden. The El Jabali Vineyard was the first OCOF (California Certified Organic Farmers) certified vineyard in Santa Barbara County.

While the fire crackles in the fireplace and radiates its warmth throughout the room, I observe a couple who have shared a common goal throughout a life that has been filled with hard work, successes and challenges. They have a thoughtfulness about their legacy and future. Their efforts and business enterprise reflect what is important to them and what they stand for.

Remember at the beginning of this story, I talked about the spirits of adventure, free thinking and entrepreneurship. These common attributes are what make this couple so dynamic and forerunners in both winemaking and conservation. They both share a love of the land and this has been the foundation in their success as vintners and conservationists. While Richard brought his understanding of the land and agriculture to winemaking, Thekla brought her love of nature and community. The arc of their commitment starts with organic farming and sustainable agriculture and includes ecological packaging, green building, wildlife protection and culminates in the slow food movement, which addresses the quality of the food we eat, where it comes from and how this affects the world. They were even honored by the Environmental Defense Center as Environmental Heroes. All the while, they make award winning wine! Richard Sanford was just added to the Vintners Hall of Fame at The Culinary Institute of America.

Their incredible commitment to our environment while operating an enlightened enterprise is just the beginning of their contribution. I always find their support and sponsorship at so many of our non profit events. They have consistently made one good decision after another to operate with integrity, be good stewards of the land, and serve humanity. Cheers!

By Holli Harmon

Reynolds Yater

"It is an interesting biological fact that all of us have in our veins the exact same percentage of salt in our blood that exists in the ocean, and therefore, we have salt in our blood, in our sweat, in our tears.

We are tied to the ocean. And when we go back to the sea--whether it is to sail or to watch it--we are going back from whence we came."

- John F. Kennedy

At least that holds true for many of us who have an inexplicable need to be near the ocean. One such person is Reynolds Yater.