Juana Maria

of San Nicolas Island

"The song that I will sing is an old song, so old that none know who made it. It has been handed down through generations and was taught to me when I was young. It is now my own song. It belongs to me." --Geronimo

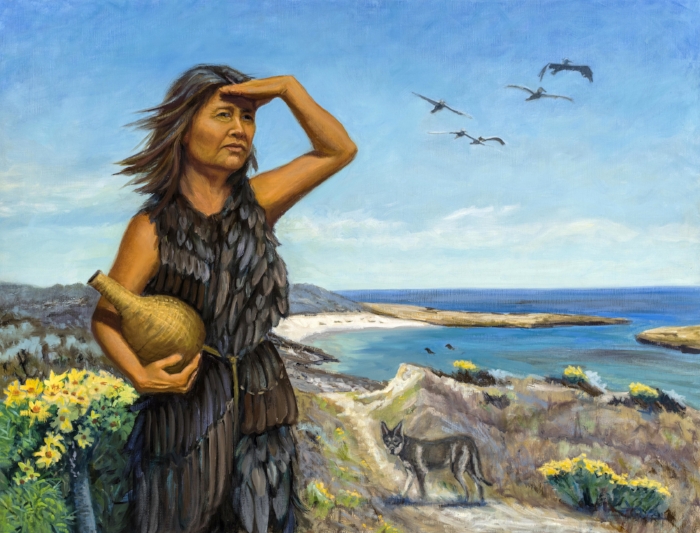

The Lone Woman 26x34 Oil By Holli Harmon See the painting at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History

Imagine growing up on remote San Nicolas Island during the nineteenth century. Children there, like everywhere, learned songs and stories about the world around them. On the island, these stories were likely about their ancestors or about the animals of their island and ocean world. The children were familiar with ocean tides and seasonal variations, and with the night sky. They knew the best places to collect kelp and sea lettuce, mussels and abalones. They knew how to fish. Perhaps a few of them even had dog companions.

On the clearest days, one can catch a glimpse of the mainland—60 miles from San Nicolas. The Nicoleños had trade relationships and social interactions with other islanders, including those from Santa Catalina. Other visitors to the island during the 1800s included American, Russian and Native Alaskan fur traders and hunters who captured sea otters for their pelts.

San Nicolas Island is where Juana Maria was born and lived for most of her life. Several historic events had a profound impact on her life. In 1814, perhaps close to the time that she was born, a group of Kodiak hunters came to the island and fought with the island men, killing most of them. Juana Maria must have grown up in a community that remembered this catastrophic incident and grieved for their loved ones. In the 1830s, she became pregnant and gave birth to a son. Soon after, in 1835, the small remaining community, just eighteen people, was brought back to the mainland as directed by the Mission fathers. As the story goes, Juana Maria stayed behind when she realized that her son was not on the ship. She later recounted that the child did not survive. And so, that is how she came to live on the island alone. For the next eighteen years, she would continue to make her subsistence-based living on her island home without contact from the outside world

On the mainland, these years were a time of great change. The Mission era saw the drastic decline of the Indian population, in part due to disease. After the Mexican War of Independence in 1822, Spanish rule ended and California became a Mexican territory. With Mexican land grants, cattle ranching became a way of life for many families. The Mexican American War of 1846-1848 ended with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The California Gold Rush began in 1848, and California achieved statehood in 1850. The City of Santa Barbara was founded the same year, with some 2,000 residents.

In 1853, Captain George Nidever, sailed to the island at the request of the Mission to find her. According to Nidever’s accounts, he and his small crew encountered Juana Maria and also spent several days there hunting otters. They found her to be in good spirits, living with her dog companions.

When Nidever brought her to Santa Barbara, few of the local Chumash may have been familiar with her language.The Nicoleños who had left the island eighteen years earlier were taken to San Pedro and they dispersed in the Los Angeles area. They may not have known of her rescue from the island. Today, researchers believe that her language was related to language groups found to the south. Genetic evidence suggests there was intermarriage between groups of the northern and southern Channel Islands as well as the mainland.

In Santa Barbara, Juana Maria lived with Nidever, his wife, Sinforosa and their children. Juana Maria was baptized and received the name that we know her by today; her Indian name is unknown. By all accounts, she happily welcomed her transition to life in Santa Barbara. She shared her songs and had many visitors, including the mission padres, who always found her to be in good humor. However, after only a few weeks of living on the mainland, she became ill and passed away. She is buried in the mission cemetery.

Her life story is unique and remarkable; she survived on her island alone for nearly two decades. As one of the last surviving Indians of San Nicolas, she is also symbolic of the decimation of a culture.

Researchers today continue to learn more about nineteenth century life on San Nicolas Island through archaeological evidence and the detective work of searching through historical records. Recent excavations by archaeologists on San Nicolas Island have revealed the large cave shelter where Juana Maria most likely lived. Two redwood boxes were also discovered that may have belonged to her and contained items such as abalone pendants, knives and fishing implements, and small stone carvings of animal figures.

"I am an old woman now...and our Indian ways are almost gone. Sometimes I find it hard to believe that I ever lived them."--Waheenee, Hidatsa

To learn more about San Nicolas Island and Juana Maria there are several resources: The National Park Service Blue Dolphin site includes links to information about the Scott O'Dell book, Island of the Blue Dolphin, as well as information on recent research. Absalom Stuart’s 1880 article, A Femal Crusoe, recounts conversations with George Nidever. Research on what happened to the Indians who left San Nicolas Island in 1835 is available in a paper by Morris, Johnson, Schwartz, Vellanoweth, Farris and Schwebel: The Nicoleños in Los Angeles: Documenting the Fate of the Lone Woman's Community.

See the painting at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History

Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History

Chumash Indian Hall Open everyday 10-5pm.

The Portrait Painting Process

Holli became increasingly intrigued with the story of the Lone Woman after conversations with archaeologist Steve Schwartz. Schwartz discovered the large cave shelter where it is thought that Juana Maria lived. In creating her painting of Juana Maria, Holli began by drafting a series of sketches based on first hand descriptions of the Lone Woman. She also conferred with anthropology and historian colleagues who discussed different characteristics including facial structure and variation in facial characteristics. The depiction of Juana Maria’s clothing is based on descriptions by Nidever of the feather cloak that she was wearing at the time of his visit to the island.

By Katherine Bradford